Tip of the month

On this page, you can find a monthly tip for diversity-sensitive and diversity-oriented university teaching. We would be happy to publish your personal advice or to address one of your questions.

The development of a diversity-oriented university culture requires that various needs, prerequisites and demands are considered, particularly in university teaching and in exam situations. With our advice, we would like to provide practical suggestions and stimulate reflection on diversity. For further information, feel free to contact us.

A variety of events are held at JGU apart from actual courses: academic conferences, lecture evenings, continuing education workshops, first semester welcoming ceremonies, graduation celebrations and institution summer festivals. Reasons for and important tips on diversity-sensitive event planning can be found in tip 06/2021 below.

As already mentioned in the chapter on diversity-sensitive planning of events, the following questions and ideas, though not an exhaustive list, should help you reflect on the process. Not all issues mentioned are relevant to every type of event. If you have any questions, need further advice or would like to make any additional suggestions, please feel free to contact us at diversitaet@uni-mainz.de.

Interaction – some questions speakers/event hosts should ask themselves

- Am I aware of my own unconscious biases?

- Am I aware of my own potential position of privilege?

- Am I aware of the structures and disparities of power in society?

- What behaviors do I find irritating in my participants and why?

- Have I sufficiently prepared myself to adequately counter any racism/group-focused enmity or discriminatory remarks made by the audience?

- Have I adequately prepared for the fact that not all of the exercises I plan to include in my event may be practicable for people with disabilities or mental illness?

- Have I adequately prepared for the different levels of knowledge and skills of my participants?

- Have I prepared for participants from different disciplines, contexts, and from different “career stages” who will be attending my event?

- Have I adequately taken into account that differences in status and hierarchy may exist between the participants of my event, which could challenge cooperation or open discussion at the event?

- Am I aware that if I plan exercises/warm ups etc., people have differing thresholds for closeness/distance and differing physical capabilities?

- Am I aware that language barriers may arise, and can I accommodate these if necessary?

- Am I aware that there may be moments (depending on the topic of the event) that may bring back very painful memories or be uncomfortable for my participants?

- Do I respond appropriately to the various participatory norms?

- Will I be incorporating different methods into my event and, hence, accommodating various styles of learning?

- Will I be ensuring participation that is sufficiently tolerant of mistakes?

- Will I be affording people the space to express their needs (e.g., support options) without embarrassing them in front of the group?

- Online events: Will the participants require technical equipment that I need to organize in advance (e.g. printers) or should I adapt the exercises so that the participants can do without this equipment?

- Am I reinforcing stereotypes in my choice of visual aids?

- Am I mindful of employing language that is non-discriminatory?

Tips for the greeting and the introduction

- You can ensure gender inclusiveness in your opening address in a number of ways, for instance, by holding a personal pronoun round, creating appropriate name tags, and, in German, by employing the Hamburger Sie...

- Establish rules of the game (e.g., confidentiality, communication that is as non-discriminatory as possible, face-to-face discussion, tolerance of mistakes, feedback rules, and, in the case of online events, instructions on how to speak to the group, use of the chat function and utilization of the camera).

- For some topics, it may be useful to indicate that some issues may be sensitive and difficult to discuss.

- You should, as transparently as possible, let participants know about available information and support services.

- For instance, it is recommended that you let people with chronic back problems know that they can take short breaks or move around for a brief period of time.

- Announce the goals and schedule of the event and also when breaks are scheduled (have you planned an adequate number?).

- It may make sense to explain which aspects of the topic the event does not touch upon and why.

- Let participants know you can be approached for questions.

Feedback tips

- Let participants know why feedback is useful and needed, and how it can help with future events.

- Respect feedback rules.

- Be sure to specify a contact person on site to receive feedback after the event once you have left.

- Give participants the opportunity to also share feedback anonymously.

A variety of events are held at JGU apart from actual courses: academic conferences, lecture evenings, continuing education workshops, first semester welcoming ceremonies, graduation celebrations and institution summer festivals.

Planning these in a diversity-sensitive will require you to design them to meet, as far as possible, the diverse needs of the audience, to reduce barriers to inclusion and to create a welcoming culture. Achieving this means finding solutions that benefit as many people as possible in the spirit of universally inclusive design, while also addressing the specific challenges presented by minority groups.

Being mindful of such issues in event planning is both relevant from the perspective of equality and a sign of professionalism, and this will help to ensure that the event runs smoothly. Diversity-sensitive event planning can be approached at organizational, methodological, and content-related levels. You should ask yourself the following questions (not an exhaustive list) to aid in planning. Not all issues mentioned are relevant for every type of event. If you have any questions, need further advice or would like to make any additional suggestions, please feel free to contact us at diversitaet@uni-mainz.de.

Tips on conducting and following up on events will follow in August.

Topic selection and formats

- Did you consider different perspectives when selecting your topic?

- Please consider whether you can/should avoid replicating traditional normative expectations or stereotypes when choosing your topic.

- Does your choice of topics take into account the current state of (scholarly) debate and/or recent developments in society?

- Is your topic relevant to a diverse participant/audience group?

- Does the format of the event reflect the various needs of the participants/audience and is it topic-related?

- Does the format allow the audience to participate properly, and is this possible in a variety of ways?

- Does the format of the event involve any specific rituals/customs that might require explanation?

Selection of speakers/event moderation/individuals involved in conducting the event

- Do the speakers/moderators possess the required diversity-related skills (on the thematic, content-related, methodological, organizational levels)?

- Do the speakers/moderators employ non-discriminatory language?

- Are speakers/moderators willing to use and provide (teaching) materials that are as accessible as possible?

- Are the speakers/moderators able and prepared to react appropriately to potential disruptions/discriminatory remarks?

- Who will be speaking on which topic? Who needs to be heard on the issue raised?

- What criteria are being used to select speakers, moderators, and panel guests?

- How have the roles of those responsible for conducting the event been assigned?

- Have the speakers been adequately briefed on the details of the opening words of greeting?

Scheduling

- Have you taken non-Christian holidays into account in scheduling?

- Have you taken holidays and daycare closing times into account in scheduling?

- If the event is being held in the evening, how will you do your best to ensure that people who care for others will be able to participate?

- If the event is going to be held online, will it be possible to schedule the event so that people in different time zones can participate?

- Do you need to consider particular safety issues for in-person evening/weekend events (e.g. consider illumination when choosing venues, inform security personnel that emergency assistance may be required)?

- Have you factored in sufficiently long break times?

Public relations/acquisition of participants/registration procedure

- Have you chosen several communication channels to publicize the event, e.g. posters, flyers, mails, social media, homepage, oral announcements, to ensure that a wide range of people find out that it is being held?

- Consider whether the way you publicize your events means you are always targeting the “same people”.

- Have you released such publicity in good time and is it accessible?

- Is the publicity worded to suit the target audience (e.g. interdisciplinary audiences, expert audiences, interested members of the public, persons familiar with university customs, first-year students, older and/or younger persons)?

- Do you need to provide information about the event in multiple languages?

- Is the imagery employed diversity-sensitive?

- When registering, are participants given the opportunity to indicate their preferred personal pronoun/form of address?

- Will you actively tell participants in advance how JGU might be able to support their participation in the event (e.g. participants with a disability/chronic illness)?

Room planning/ technical equipment/materials/support/facilities/catering

- Is the venue as accessible as possible (elevator, signage system, accessible WCs nearby, sufficient space)?

- In the event of last-minute venue changes, how can you ensure that people for whom more complex advanced planning is necessary to ensure their presence are given adequate support?

- Have you considered the needs of people who are unable to stand at a “normal” stand-up table for breaks; for example, at networking events/conferences?

- Is the lighting in the event room adequate for people with visual impairments?

- Is the design of the presentation materials/posters sufficiently large and is the contrast adequate?

- Will the acoustics of the room be a problem for people with hearing impairments?

- Can the height of the lectern be adjusted?

- If the event is being conducted from a stage, is it accessible via a ramp system?

- Does the seating give people enough room to move around?

- If catering is going to be provided, will there be sufficient variety (vegan, vegetarian, halal, gluten-free, allergies, food intolerances etc.) with clear labeling?

- Is it possible to hire a catering firm that employs inclusive practices?

- Is there any way of relying on fair-trade products?

- Will your name tags have the option to indicate a person's preferred pronoun?

- Is sign language assistance required?

- Is material needed by participants in preparing for the event accessible and affordable?

- Depending on the topic, you should consider the likelihood of incidents at some events. Will you need to prepare a “safety concept”, and has everyone been briefed on this?

- Will you need to record the event to allow people to experience it after it has taken place?

Feed-in and preparation of participants

- Will you need to consult participants about their different levels of knowledge and expertise?

- Do you plan to inform the participants in advance about the schedule of the event, including break times (if necessary, also in a foreign language)?

- Have you proactively informed participants about issues of barrier-free access?

- Are childcare services required and feasible?

- In the case of online events, have participants been informed about the technical requirements for participation? Can/must rental equipment (cameras) be offered beforehand?

Does the format give participants the chance to submit (feed in) their own important points/questions in advance?

My name is Nina Becker, I have been blind since birth and am currently studying educational science and sociology at JGU Mainz. In my studies I work with a laptop and a so-called Braille display, which converts the screen contents of my laptop into Braille with the help of a software called Screenreader. In this way, I can read texts independently and take notes on the normal laptop keyboard using ten-finger typing, write papers, and much more.

The digital semesters have brought new challenges for me, as a lot is done via video conferencing and is therefore very visually based, so I often have difficulty following or comprehending everything. In face-to-face teaching, I always introduced myself personally to the lecturers at the beginning of a semester so that they knew I was there and I could contact them if I had any questions or problems. Most of the time, I was provided with lecture slides in advance so that I could convert them into a form I could read and thus follow the lecture better. If there were any difficulties or pictures, graphics, etc., I could simply ask one of my fellow students or the lecturer gave me a short explanation.

In the digital semester, this is not that easy, since I no longer have direct contact with lecturers and students. I don't have an easy opportunity to introduce myself to the lecturers in person, and writing a corresponding email before the start of the event sometimes seems kind of weird or intrusive, so I've avoided this so far. Also, in case of difficulties, I can no longer just quickly ask someone, but would have to first seek contact by mail or phone. This is much more time-consuming and is a bigger hurdle for me - especially if I can't get support immediately, but have to wait for a response.

Another challenge for me is that digital events do not run through an internal university system, but each lecturer uses different systems, which are not all equally usable for me. So, for every event, I had to first familiarize myself with a corresponding conferencing system and figure out on my own how it was usable for me. The fact that all of these systems are largely optically based and work primarily with icons, images, etc., made it even more difficult for me. Also, in the individual systems, I don't get the lecturer's displayed presentation read out by my program, so I need it as an extra file to work with simultaneously. Some other functions of the videoconferencing systems, such as chat, are also mostly not usable for me, or only to a limited extent.

So it takes a lot of patience from my side and helpfulness and accessibility of the lecturers in the digital semester to enable me to study halfway smoothly. It helps me a lot when lecture slides are additionally made available as downloadable documents so that I can read and use them at all. In addition, I depend on the consideration and understanding of the lecturers when something doesn't work properly for me due to technical reasons and the lack of accessibility of the conference systems. If problems arise, I am happy to maintain a lively exchange with lecturers and, if necessary, ZDV, in order to find a suitable solution in a short time. In the future, it would make things a lot easier for me if the lecturers could decide on one or two conference systems to be used at the JGU, so that I could concentrate on their operation and not have to constantly learn new systems.

To be accessible to all, a video must be...

- incorporated into a website in a barrier-free way

- playable using a media player accessible for everyone

- subtitled

- accompanied by an audio description

- translated into sign language.

Videos that are barrier-free in this way are primarily designed to make media content accessible to people with visual or hearing impairments. However, subtitling can also benefit non-native speakers or mobile users who do not have headphones available.

In the following video, Adrian Weidmann, a member of staff at the Center for Audiovisual Production (ZAP) at JGU provides a practical example to help others with the design, creation, and implementation of livestreams that are accessible for all. The video, which covers four factors (speaker, translation into sign language, presentation slides and subtitles), was streamed live at INKLUSIVA (the RLP Inclusion Fair) in September 2020.

In the second part of the video, Adrian Weidmann explains how to use Panopto, MS-Powerpoint and MS-Stream to automatically generate subtitles. All three programs are free for use by JGU members.

Center for Audiovisual Production at JGU: https://www.zap.uni-mainz.de/

Adrian Weidmann (Center for Audiovisual Production) on how to create accessible videos: https://video.uni-mainz.de/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=feacca78-12b3-4a4e-9cf3-acd20168c3a9

Guideline “Barrierefreie Online-Videos" created by the BIK project (accessible information and communication for all): https://bik-fuer-alle.de/leitfaden-barrierefreie-online-videos.html

Does this topic even apply in times of online courses? Experience has shown us that it does – sexual harassment is not always expressed physically, such as through unwanted touch, disregard for personal space, or even sexual assault or physical violence.

It can also be verbal, with misplaced questions about one’s sex life, jokes, intrusive comments on appearance, sexualized labels, suggestive comments, requests for sexual favors, or non-verbal in form of suggestive gestures, emails with sexual content, the posting of pictures, videos, etc. on social platforms.

Sexual harassment if often an expression of rivalry and lack of respect, and all genders can be guilty of it. According to studies¹, women are affected most often, but of course, men and can also be targets (link).

If you as a member of the teaching staff observe sexual harassment in your courses (but at the very latest, when you receive a direct complaint), you are obligated to act. This is stipulated by JGU‘s Policy on the Protection against Sexual Harassment (link).

Handling sexual harassment requires a highly professional attitude, especially regarding advising competence, conflict resolution skills, and your level of knowledge on the topic, in addition to being able to detect and correctly identify sexual harassment. The following information is meant to offer support and first impulses. We are happy to help if you have questions.

Prevention

Clear Position Against Sexual Harassment

- At the start of your course, clearly identify what sexual harassment is. You can find examples in the handout from the Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency (link, in German).

- Make it clear that you will not tolerate sexual harassment.

- Explicitly reject the trivialization of sexual harassment as jokes or misunderstandings.

Removing the Taboo around Sexual Harassment

- Address the topic openly and as removed from an actual event as possible.

- Communicate clearly that you are available as a contact person for affected persons.

- If possible, name others who can serve as primary contacts (of different genders).

- Get an overview of possible risk factors, such as infrastructure, times

- Encourage the development a respectful community.

- See the tip regarding physical contact (11/2017).

Concrete Event

- Take action if you observe sexual harassment yourself.

- Take information from affected persons or third persons seriously.

- Keep a record of information from third persons or affected persons.

- Keep confidentiality and be discrete and ask others to do the same.

- If you need support, you can find points of contact in JGU’s Policy on the Protection against Sexual Harassment (link)

- Offer affected persons your support and draw their attention to existing internal (link) and external (Women’s Emergency Hotline, in German) support options.

- Allow the affected person to have the prerogative for interpreting the situation.

- Take action in close collaboration with the affected person.

- If someone feels acutely threatened, contact the Central Services’ Security Department (link, in German).

- Take precautionary and protective measures (for potential other affected persons, too) and, at the same time, protect the suspected perpetrator from premature condemnation.

- Be transparent toward the affected person regarding your own questions – making notes, documentation, further actions.

- Avoid confronting affected and accused persons.

- Act in coordination with your superiors, the Equality and Diversity Office, and, if necessary, Legal Affairs.

¹ Further information on the studies:

- Gender-based Violence, Stalking and Fear of Crime. Country Report Germany (link, pdf)

- Sexual Harassment in the University Context – Gaps in Protection and Recommendations (link, in German)

- Handling Sexual Harassment at the Workplace – Solution Strategies and Measures for Intervention (link, in German)

For many employees, working from home was part of everyday life even before the Corona pandemic. Others were abruptly and involuntarily forced to create a workplace at home and create new processes and structures to make an effective working environment possible.

Home and office – it sounds like a contradiction. And it is true – the line between work and private life is fluid. This new work reality brings a lot of organizational challenges, in addition to all of the insecurities, worries, and fears which accompany us at this time.

As a member of the teaching staff, please be aware that your co-workers and students are also in an unusual situation and that people possess different capacities for handling (emotional) stress and coping with difficult situations (resilience). Depending on one’s life and living situation, care responsibilities, financial background, social network, and individual health, etc., we are all affected by these changes and this uncertainty to differing degrees and are therefore faced with different challenges.

For these reasons, please try to have patience for possible delays in work processes and be patient with yourself, too. We seem to forget from time to time that we are currently in a pandemic, not taking part in a self-optimization challenge.

Support your Students with Their Studies at Home:

- Let your students know that you are aware of the exceptional situation.

- Don’t be afraid to let your students know that this kind of teaching is new for you, too, and you also require time to get used to it.

- Take into account that access to libraries and quiet workspaces might be limited.

- Keep in mind that your students’ workspaces might be equipped very differently – not only in terms of technical equipment, but also regarding available space, internet speed, noise level, the possibility to speak undisturbed…

- Let your students know that you have understanding for possible late work.

- Don’t forget that the students are also in an emotionally abnormal situation.

- People process contact bans and isolation differently. Let your students know that you are willing to listen to them, and proactively let them know about JGU’s advising and support offers. Especially students who are part of a risk group should know about these offers.

- Take into account that students who are also parents might be even less flexible (especially when holding “live classes”).

- Loosen attendance requirements, if possible, or make alternative dates and alternative tasks which can be completed offline an option.

- During video or skype conferences, make sure every student has the room to speak – careful moderation is especially important, and rules for communication can be very useful in larger chat groups (muting microphones, requests to speak via buttons, etc.).

- Keep in mind that not every student is equally comfortable with virtual communication/virtual learning.

- Pay attention to discrimination-free communication in discussion forums (for example).

- Make sure your learning materials are accessible.

- Make your learning goals transparent.

You can find further useful information for working in home office and on (current) support offers here:

Distance Teaching at JGU – Tips, Information, and Support Offers:

Link: https://www.blogs.uni-mainz.de/teaching/digital/

Support for accessible teaching from the Office of Accessibility:

Link (in German): https://www.barrierefrei.uni-mainz.de/barrierefreie-lehre/

Family Services Center – Corona and Family:

Link (in German): https://www.familienservice.uni-mainz.de/corona-familie/

Virtual Campus Rhineland-Palatinate – Recommendations for Switching to Online Teaching:

Link (in German): https://www.vcrp.de/digitale-lehre

Platform Connecting Teaching Ideas (Lehrideen vernetzen):

Link (in German): https://plattform.lehrideen-vernetzen.de/de/suche?term=corona

Data Center:

Link: https://www.en-zdv.uni-mainz.de/home-office/

The project “Healthy Campus Mainz - gesund studieren” aims to gain scientific insight on how to promote the health of students in order to create evidence-based measures to promote and maintain students’ good health. Our colleagues have put together the following tip on physical activity:

What is physical activity and what are its benefits?

The WHO defines physical activity as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure – including activities carried out when working, playing, doing household chores, traveling, and during recreational time.

The term “physical activity” should not be mistaken with “training”, a subcategory of physical activity which is planned, structured, and repeated with the goal of improving or maintaining one or more components of physical fitness. Aside from training, every other physical activity, whether recreational, for transport from one point to another, or as part of someone’s work, has a health benefit. Furthermore, both moderate and vigorous physical activity have a positive effect on one’s health:

- Increase of muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness

- Reduction of the risk of chronic illnesses (hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, various types of cancer (including breast and colon cancer), and depression)

- Improvement of bone and functional health

- Reduction of the risk of falls

- Regulation of energy balance and weight control

- Improvement of sleeping quality

- Improvement of executive function (brain processes —> ability to plan and organize, initiating tasks, control of emotions)

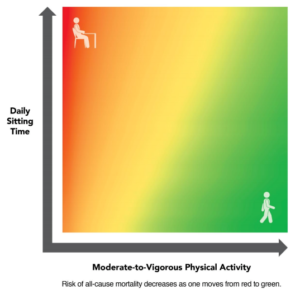

Fig. 1 Correlation between moderate to vigorous physical activity, sedentary time, and risk of general mortality (Ekelund et al., 2016)

Physical Activity Recommendations for Adults

Over the course of a week, at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity, at least 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity, or a corresponding combination of moderate and vigorous should be carried out. In order to achieve an additional health effect, adults should increase their moderate physical activity to 300 minutes per week or to an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous physical activity.

In addition, activities strengthening the muscles of the most important muscle groups should be carried out on two or more days of the week.

You can find an overview of recommendations for adults and other age groups here: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-10/PAG_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

Increasing Physical Activity for University Teaching Staff

Walking, cycling, and other types of active movement are accessible and safe for everyone,

- Take the stairs instead of an elevator!

- Change of workplace stance (standing, walking)

- Active break during a double lesson

- Active lunch break, choosing the cafeteria furthest away from your workspace

- If possible, establish active meetings with colleagues

- Take advantage of the university sports offers

- Make arrangements with colleagues to be active (jogging, cycling) before work, during the lunch break, or after work

A Diversity-Oriented Approach with the Students

Physical activity is of varying degrees of importance for everyone in our society. The reasons behind an individual’s extent of movement are often profound and difficult for outsiders to comprehend. Physical limitations, illness, social conflicts, mental pressure or fear are only a few of many reasons which can affect everyone and influence the level of everyday physical activity. Therefore, it can be complicated and challenging for university teaching staff to address this complex topic with students. The focus here is explicitly on making available the above information and emphasizing the health benefits of physical activity. It is extremely important to approach the topic from a position of wanting to take care of and respect each individual student. Every faculty should feel addressed and encouraged to make its contribution and consider how one can design active teaching components for lectures or seminars.

How can you as a member of the teaching staff incorporate this in your teaching?

Taking into account the different physical and psychological prerequisites to be able to learn, the following approaches can be helpful:

- Address the importance of physical activity during the introductory class, generate awareness, and inquire as to the students’ interest

- Offer the option to move or stand during your course

- Incorporate active breaks for movement during multiple-hour courses

- Integrate active learning content, make use of your space by having students do work at stations or in groups on campus, for example

- Develop movement rituals with the students for the beginning or end of the class

If you have further questions or would like advice, Dr. Daniel Pfirrmann is happy to help.

Dr. Daniel Pfirrmann

Institute of Sports Science

Department for Sports Medicine, Prevention & Rehabilitation

Phone: 06131 39 23571

email: pfirrma@uni-mainz.de

Literature:

Ekelund, Ulf, et al. (2016) Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonized meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. The Lancet 388.10051 (2016): 1302-1310.

Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. (2018) Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018).

World Health Organization (2010). Global recommendations on physical activity for health. World Health Organization.

The Center for Quality Assurance and Development has published a handout for speakers in the field of higher education didactics. It grants insight into how officers can be sensitized and qualified for diversity-related questions in the teaching/learning context.

You can find the handout here (Link, in German)

What is group-specific misanthropy?

Group-specific misanthropy (Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit (GMF)) is defined as the stigmatization, marginalization, and degradation of people due to attributed or chosen affiliations with a certain social group. Group-specific misanthropy can express itself in the form of xenophobia, racism, ableism, anti-Semitism, sexism, homo* and transphobia, Islamophobia, classism, etc.¹ The Institute for Interdisciplinary Research on Conflict and Violence (IKG) at Bielefeld University studies the phenomenon in a separate research cluster and has been carrying out cross-sectional studies on group-specific misanthropy in Germany since 2002.². GMF is based on an “ideology of inequality”, which, according to the researchers at the IKG, is not a phenomenon found only at the extreme edge of the political spectrum, but is a broad, widely shared opinion among the German population.⁴

How can group-specific misanthropy express itself in a course?

GMF is often associated with violent or openly aggressive behavior, but can, of course, also be expressed more subtly. From our student survey, in which students can report discrimination in JGU’s teaching and learning context, we know that students experience group-specific misanthropy in a university context, as well. This can be expressed in the classroom in the form of:

- pejorative, derogatory, generalized, or discriminatory statements towards them, fellow students or social groups in general;

- marginalization of fellow students when completing group work;

- stigmatizing and stereotypical statements in presentations or papers;

- circulation of comments expressing stereotypes;

- claiming the privileges of the established;

- instrumentalization of, for example, equality issues;

- hate speech on social media;

- provocative contributions superficially concealed as good fun;

- the promotion of topics and discussions which can be used as a platform for corresponding contributions;

- neo-Nazi symbols or clothing;

- Othering (creating differences and distance to social groups)

- insults, threats, aggressive or violent behavior.

How can you as a member of the teaching staff confront this?

Every case is different and therefore, your reaction should be different depending on severity and form of expression. For members of teaching staff, it is important for you to first get an overview of the different forms of group-specific misanthropy. As a preventative measure, you can make clear in your courses that you actively support a respectful coexistence. It can be a good idea to refer to the resolutions on tolerance at the university adopted by the Senate in 2008 (link), JGU’s diversity offers, or the different positions of the German Rectors’ Conference. It can also be helpful to make the confrontation with group-specific misanthropy a topic with colleagues and ask about others’ experiences and practical approaches. Ignoring or trivializing problematic comments or events in your courses is not the right way to react. Depending on the situation, you need to decide whether you will address the relevant behavior immediately or later in a one-on-one conversation; question derogatory statements; enter into a critical discourse about problematic contributions; argumentatively refute points made; show solidarity with the attacked person; or whether sanctions are necessary. The right words cannot always be found, but even speechlessness or bewilderment due to comments or behaviors that cross the line can be formulated. You can find information and helpful recommendations for courses of action regarding destructive discussion strategies and polemic argumentative patterns in these publications (in German):

- Antifeminismus als Demokratiegefährdung?! Gleichstellung in Zeiten eines erstarkenden Rechtspopulismus

- Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Wandzeitung "Rassismus begegnen"

The Equality and Diversity Office is happy to help and offers individual advising and support. In cases of aggressive and violent behavior, please contact the Unit for Security, Transport, and Traffic (phone. 06131 39 22345)

Further links

- State action plan against racism and group-specific misanthropy (link, in German)

- HRK: „An deutschen Hochschulen ist kein Platz für Antisemitismus (link, in German)

- Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Senate resolution for tolerance on university property (link, in German)

- Cosmopolitan universities – against xenophobia (link, in German)

Sources:

¹ See: Groß, Eva/Zick, Andreas/Krause, Daniela: Von der Ungleichwertigkeit zur Ungleichheit: Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2012, Vol. 16/17, pp. 11-18. (link, in German)

² See: https://www.uni-bielefeld.de/(en)/ikg/forschung.html

³ Groß, Eva/Zick, Andreas/Krause, Daniela: Von der Ungleichwertigkeit zur Ungleichheit: Gruppenbezogene Menschenfeindlichkeit. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 2012, Vol. 16/17, pp. 11.

⁴ Ibid., pp. 12f.

Making learning materials accessible mainly means allowing students flexibility in working with the materials. This does not only help students with disabilities or limitations, but also those who learn in a different way. Before we get to the Guidelines for Accessible Materials, we would like to give you a few ideas for how you can generally make your courses more accessible for a greater number of students.

If you require technical support for your course, the Center for Audiovisual Production is happy to help: zap@uni-mainz.de.

Podcast/Audio Recordings

Record your lecture as an audio file and make it available as a podcast.

Video Recordings

Of course, it’s even better to use video recordings with video.uni-mainz.de. You can make them available exclusively for your students and sync your slides automatically.

This helps:

• students with visual impairments

• with catching up on and repeating lessons (on bus or train)

• students with hearing impairments (who can use specific devices to listen later)

• students with cognitive impairments (who can press pause or adjust the playback rate)

Hand Out Materials Ahead of Time

Make notes and teaching materials available at the beginning of the semester. Students can then prepare better for the course depending on their special needs and can print out the slides in oversize (for the visually impaired) or read through materials ahead of time, for example.

This helps:

• Everyone

What needs to be considered when creating accessible materials?

As a rule, it’s important to know how students with impairments process the materials. Students with visual impairments, for example, might have a so-called screen reader to read material for them. A screen reader reads unformatted text from top left to bottom right. If the listener wants to hear a passage again and the text is not formatted, the only option is to listen to the entire text again. The listener can only “turn pages” by fast-forwarding or rewinding, without any indications for when they should stop again. By implementing a few simple things, you can greatly facilitate your students’ learning:

1. Structure Your Text

Word: Use the style function in Word: Alt+Ctrl+Shift+S → Options → Select styles to show → Choose styles → All styles. Mark headings, lists, bullet points, links, quotations, etc. as such. For the screen reader, the style will work like bookmarks and allow users to jump to relevant sections.

PowerPoint: Unfortunately, PowerPoint does not offer any styles. Instead, you will have to make sure the reading direction is correct when creating your slides. You can do this under Home → Arrange → Selection Pane. Additionally, you should title your slides. The titles will then function like bookmarks.

PDF: As a rule, we recommend not using PDF. The limited display options do not allow students to adapt the content to their needs. However, if use of PDF is unavoidable, make sure you check ACROBAT →Default settings→ Accessibility and Document structure tags for accessibility when exporting from Word or PowerPoint.

2. Select the Language

In order for the screen reader to know which language to read in, you have to select the language of the document. You can do that by selecting Home →Language. If you have multiple languages within your document, in quotations, for example, select the language anew for each respective paragraph.

3. Alt Texts

Try using pictures and diagrams parallel to the text instead of as an exclusive form of information. If you do use pictures and diagrams, include a comprehensive alt text for screen readers to read. If a picture is only decorative, you can select that option in the alt text box, so it is apparent for everyone.

4. Tables

Tables should be as clear as possible. If your tables stretch across several pages, activate the header row for every new page. This makes it easier to keep an overview, and students have to turn fewer pages.

5. Scanning Texts with Character Recognition

If you scan texts from source materials for your students, use software with character recognition (such as FreeOCR or Omnipage). This helps display the text better, and also allows for a search of the text.

6. Contrasts

Make sure you use the highest possible contrast when choosing text and colors. Black on white is the best option. If you want it to be more colorful, you can use the program Color Contrast Analyser, for example, which you can download by clicking on the following link: https://developer.paciellogroup.com/resources/contrastanalyser/

7. Check Your Documents

Microsoft Office now offers an accessibility check. You can find it under Review → Check Accessibility.

You can find further instructions and information here:

- Accessibility: Inclusive E-Learning (link in German: https://www.e-teaching.org/didaktik/konzeption/barrierefreiheit)

- Hand-out for the creation and implementation of accessible materials in teaching (link in German): https://www.uni-marburg.de/de/studium/service/sbs/sehgeschaedigte/hochschullehre.pdf)

- Guidelines for the creation of accessible materials - Office for the Preparation of Accessible Teaching Materials – University of Kassel (link in German): https://www.uni-kassel.de/themen/fileadmin/datas/themen/Literaturumsetzung/Leitfaden_1315_Homepage_3.pdf)

Author: Anna Heym (Center for Audiovisual Production)

If diversity-oriented teaching takes into account students’ various (learning) prerequisites, experiences, and learning levels and aims for everyone’s participation, how can members of the teaching staff do justice to this not always visible or noticeable diversity during the methodic-didactic planning of courses?

It is certainly a good idea to take leave of the “one size fits all” principle and meet student diversity with a diverse range of learning and teaching methods in order to increase possibilities for participation and strengthen everyone’s learning and study success:

- the implementation of different formats(presentations, individual and group work, panel discussions, class discussions, …) increases the options for participation;

- varying use of media and a variation of material to work on (pictures, audio, text, …) appeal to different types of learners;

- interactive learning methods(such as quiz tools, virtual laboratories, blogs, …) offer more options for participation and increase motivation;

- e-learning/blended learningallows students to learn more flexibly (regarding their time and space);

- teaching learning strategies can make independent studying more successful;

- making different examination formats available and giving students the option to complete work in a variety of ways allows students to use their skills and abilities effectively;

- ..

If you want to expand your repertoire of methods or exchange ideas with colleagues, you can find plenty of options for support and networks at JGU:

- The collaborative project “Connecting Teaching Ideas” (“Lehrideen vernetzen”) has created an inter-university platform for the transfer of didactic concepts (link in German): https://www.lehrideen-vernetzen.rlp.de/

- The Center for Quality Assurance and Development’s university didactics offers individual teaching advising and collegial coaching (link in German): https://www.zq.uni-mainz.de/hochschuldidaktik/

- The Evaluation Association of Institutes of Higher Education Südwest imparts teaching competencies through its university didactics offer (link in German): https://www.hochschulevaluierungsverbund.de/das-hochschuldidaktische-angebot-des-hochschulevaluierungsverbundes/

You can also find helpful tips and information outside of JGU:

- The Toolbox Gender and Diversity in Academic Teaching has practical hints for diversity-oriented teaching: https://www.genderdiversitylehre.fu-berlin.de/en/toolbox/index.html

In her current (2019) contribution to the debate about diversity-oriented university teaching, Minna-Kristiina Ruokonen-Engler focuses on the topic of biography sensitivity. According to her thesis, university teaching is aimed at the “construed normal student” and does not take student diversity into account. This leads to a social imbalance and could lead to discrimination and disadvantages for students.

She proposes countering this with a biography-sensitive approach to university teaching, which she defines as the conscious confrontation with both teaching staff and student biographies, as well as the critical analysis of everyday experience. Consciously engaging with these experiences can provide insight into how an institution acts, includes, and where it creates disadvantages.

How can university teaching be made biography-sensitive?

The author describes research projects on student biographies, which can be carried out in the social science subjects. Data collection and evaluation are to be analyzed against the backdrop of students’ reflection on the own biography.

How can this approach be implemented in subjects which do not primarily deal with questions of social justice, anti-discrimination, diversity, etc.?

In these cases, students’ diversity can be taken into account on a methodological level, or when interacting with students: when planning courses (accessibility, care responsibilities, language barriers), for example. The interaction with teaching material and experience-based (everyday) knowledge, which is often called “non-academic knowledge” (Ruokonen-Engler 2019, 549), can be very insightful. Biographical experiences can, however, be characterized by experiences with discrimination or be discriminatory themselves; therefore, students and teaching staff must critically reflect upon them. The author advocates for further development of teaching formats, as well as other pilot projects which tackle the approach of biography-sensitive university teaching.

How do you handle this topic? We would be happy to hear from you!

Literature:

Ruokonen-Engler, Minna-Kristiina (2019). Biografiesensible Hochschullehre. In: Kergel, David & Heidkamp, Birte (Hg.). Praxishandbuch Habitussensibilität und Diversität in der Hochschullehre (539-558). Wiesbaden.

Projects:

Biographieorientierte und phasenübergreifende Lehrerbildung in Oldenburg (OLE+) (Link, in german)

For our November 2018 tip, we reported on student experiences with the “Hamburg Sie” – addressing someone with their first name and the formal “you”. This month, we will again be discussing how to handle gender diversity in the classroom and want to bring attention to the recent brochure trans. inter*. non-binary. Shaping Gender Aware Teaching and Learning Spaces at Universities. (trans. inter*. nicht-binär. Lehr- und Lernräume an Hochschulen geschlechterreflektiert gestalten).

The brochure was developed as part of the project Non-Binary Universities. Measures to Strengthen Gender-Diversity at Austrian Universities and is meant to help universities become more inclusive spaces.

The authors emphasize recognizing gender diversity and understanding gender as non-binary.

How do I address someone (in class or in an email, for example)? Which pronouns do I use? What’s the difference between official and preferred personal details such as names? Which norms are expressed through the current public toilet situation?

The brochure answers commonly asked questions and suggests specific courses of action for teaching. The checklist in the brochure encourages self-reflection regarding one’s own teaching:

Download:

trans. inter*. nicht-binär. Lehr- und Lernräume an Hochschulen geschlechterreflektiert gestalten. Wien 2019. (pdf, in german)

In April 2019, an exchange with young JGU researchers took place against the backdrop of a diversity workshop carried out in cooperation with the Gutenberg Teaching Council (GLK). The topics were the everyday reality in the PhD phase with its challenges and stumbling blocks, and the doctoral students’ needs. The relevance of individual, good supervision during the PhD phase was discussed at length. It’s worth reflecting on what good supervision is from a diversity perspective:

Who’s doing their doctorate with me?

- Who do I think is eligible for doing their PhD?

- Which criteria am I using to make my judgements?

- What do I expect of students / people who would like to earn their doctorate before they are admitted to a doctoral program?

- Do I encourage students to pursue a doctoral degree if they have a chronic illness, are responsible for caring for others, or do not fit my normal image of doctoral students?

What supervisory agreements do I make with doctoral students?

- Do I give the doctoral students a chance to have a say in such agreements?

- Are my expectations clear and understandable?

- Which requirements and expectations do I have regarding meetings (documenting work stages, etc.)?

- What kind of support can my doctoral students expect from me?

- Is my supervision tailored to fit individual needs?

- How do I react when doctoral students do not receive financial support (scholarships, etc.) and have to work “on the side”? Do such circumstances influence the quality of my supervision (information on symposia, tips regarding literature, active integration in academic discourse, etc.)?

What is my supervisory relationship to my doctoral students like?

- Is open and honest communication possible even when issues such as research setbacks or personal problems occur?

- How do I express criticism and recognition?

- Are my suggestions for meetings tailored so even doctoral students with children or work can take advantage of them?

- How do I prepare my doctoral students for the scientific community’s unspoken rules?

- How do I handle irritants in the way my doctoral students dress or act?

- How aware am I of power and status?

- Am I aware of all the JGU support offers which could be useful for my students?

- ...

Information & Support:

- Family Services Center

- Career Perspectives for Postdocs (link in German)

- Young Female Researchers Program

- Getting a Doctorate from JGU

- Doctorate from Johannes Gutenberg University. Senate Recommendation, January 20, 2012 (PDF in German)

- Welcome Center for International Scholars

- Rhineland-Palatinate Re-Entry Funding

Further Reading:

Baader, Meike Sophia, Svea Korff und Wolfgang Schröer (20162). Ein Köcher voller Fragen – Instrument zur Selbstevaluation. Paderborn. Link (pdf in German)

Mucha, Anna und Christian Decker. Der Dissertationsprozess als explorative Lernumgebung: Warum erfolgreiches Promovieren (auch) eine Frage der sozialen Herkunft ist. In: Zeitschrift für Diversitätsforschung und -management 2/2017, S. 29-34.

Practical laboratory work is an important part of the study of natural sciences and poses special challenges for teaching staff and students. Consistently keeping to the highest standards of safety and hygiene is vital for laboratory work, as are clear instructions and good supervision for individual and group work. Against this backdrop, how can you have a diversity-oriented focus in laboratory work?

The different activities in the lab, which often must be carried out in small, constrained spaces and are therefore not very accessible, can have an exclusionary effect on people with disabilities (see also the Manual for Teaching Chemistry for Students with Disabilities from the American Chemical Society Committee on Chemists with Disabilities).

In some cases, it may seem difficult to combine meeting the current safety standards in order to minimize danger to participants, make participation possible for all of the students, and fulfill the educational requirements – all at the same time. It’s important, however, to look at each case carefully and search for individual solutions in order to minimize exclusionary structures.

Here’s a successful example:

A student in a wheelchair, and therefore with a limited range of motion, was assigned an assistant for her time in the lab. The assistant handed her chemicals and the student carried out experiments mainly on her own. For the time she spent in the lab, a custom-created emergency plan was in place, which provided the possibility of evacuation, if necessary.

Temporal limitations can also be a great hindrance to students. For example, laboratory work which is scheduled for nights or on weekends is hardly or not at all possible for students with caregiving responsibilities or students who must finance their studies themselves.

Since the revision of the Maternity Protection Act (Mutterschutzgesetz - MuSchG), valid since January 1st 2018, pregnant and breastfeeding students who are obligated to complete practical courses within the framework of their studies are also protected. The MuSchG regulates, among other things, work times, (prohibiting night- and overtime work), handling hazardous substances, keeping the protection period before and after delivery of a child (see also the Guidelines on Maternity Protection of the BMFSFJ (in German) and the JGU Guidelines for Pregnant and Breastfeeding Students (in German)). For questions on maternity protection for students at JGU, please turn to the Family Services Center.

Students who wear a headscarf can continue to do so in a laboratory environment. However, it is important for you as a member of the teaching staff to call attention to and enforce the security regulations regarding acceptable clothing for working in a lab (material / length).

We would be grateful for more examples illustrating how you as a teacher handle different aspects of diversity.

Further reading and practical examples can be found here:

Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (2018). Leitfaden zum Mutterschutz. (Link)(Maternity Protection Guidelines, Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth)

Classen, Georg. Eine unterfahrbare Innovation. In: Zeitung der Freien Universität Berlin, (3-4) 2002. (Link)

Götschel, Helene; Metzger, Max & Anja Sommerfeld: Gender und Diversity im Physikpraktikum/Physiklabor. In: Gender und Diversity in die Lehre! – Strategien, Praxen, Widerstände, Konferenz 24. – 26.11.2016 Freie Universität Berlin.

Miner, Dorothy L.; Nieman, Ron; Swanson, Anne B. & Michael Woods (2001): Teaching Chemistry to Students with Disabilities: A Manual for High Schools, Colleges, and Graduate Programs 4th Edition (American Chemical Society Committee on Chemists with Disabilities).

Schwan, Clemens 2009. „Muss es denn unbedingt das Chemie-Studium sein?“ – Warum die Antwort nur ein klares „Ja“ sein darf. Untersuchungen und Referat zum Themenbereich „Studierende mit Behinderungen in experimentellen Praktika“. 23. Bonner Sicherheitsseminar 2009 der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Sicherungstechnik/ Angewandter Umweltschutz.

Support from JGU:

The Federal Ministry of Education and Research defines the goal of the German Federal Training Assistance Act (BAföG) as:

“Bafög enables young men and women to choose the training that suits their personal interests, irrespective of their families' financial means” Link, in german)

This is a goal that has not been achieved yet and is highly relevant in the current university-political, political, and media discourse (see the Wiarda-blog, among others (link in German)). Raising the aid ceiling, housing allowance, and the parental allowance limit are being considered for the reformative 2019 plans. Getting into debt, worries that financial support will not be granted for studying abroad, and the complicated application process can act as obstructions. For example, the regulations stipulate that vocational training must be begun before someone has reached thirty years of age. For graduate degrees, the age limit is 35 years. However, there are exceptions that are often not well known. The age limit shifts, for example, for parents with children or for those who have earned their university entrance qualification through “second-chance education”. Students who have health problems, are responsible for family members, or fail a final exam can receive financial aid past the regular financial aid period. Under certain conditions, it is possible to apply for BAföG independent of parents. Students who were gainfully employed after completing vocational training fall into this category, for example.

You as a teacher can bring your students’ attention to the following support offers and contact persons regarding the BAföG topic:

- BAföG in German sign language (link)

- Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Everything you need to know about the BAföG on first glance. (Link in German)

- Financial Support Office, JGU Mainz. (link in German)

- Informational flyer, BAföG. (link in German)

Further financial support offers from JGU:

Within the framework of the working group “Social Pedagogy” and beginning in the winter semester of 2014/2015, we have regularly offered bachelor and master seminars on the topic of “Diversity” at the Institute for Educational Science. During these seminars, we focus on theoretical and practical perspectives on diversity. “Diversity” is derived from the Latin word “diversitas” and means difference.

Taking a Close Look at (our own) Practices of Differentiation

Diversity-approaches perceive people on the basis of categories (Emmerich/Hormel 2013: 184). Categories are, for example, “nationality”, “ethnicity”, “country of origin”, “age”, “physical constitution”, “gender”, “sexual identity”, or “ideology”. Some of these categories are addressed in the General Act on Equal Treatment (AGG), which came into force in Germany in 2006. In the seminar group, we reflect on sorting people into these and other categories. These categories don’t exist, per se, rather it is we who define, based on classifications, when someone is considered “learning impaired”, for example. Differentiating based on so-called “ethnicities” is also problematic – what does “ethnic” mean? As cultural anthropologist Elisabeth Timm (2000) put it, “it’s always the others who are ethnic”. “‘Koreans in Los Angeles’ are ‘ethnic’, ‘Chinese in New York’, ‘North Africans in Lyon’, ‘Jews in France’ or ‘Turks in West Berlin’” (ibid, 364). Calling something “ethnic” changes it. It creates an “us” and “them” mentality within the framework of a particular understanding of ‘normalcy’. In this seminar, we try to become sensitized to these differentiation practices. We, too, add to alienation, social inequality, and exclusion with the decisions we make (Kourabas/Mecheril 2015). It is these practices of differentiation we aim to become aware of and examine if they lead to social inequality and a lack of participation. This central element of the seminar can be described as reflexive diversity-competence (Beate Aschenbrenner-Wellmann, 2009).

Opening Organizations

At the same time, we are working on diversity on the organizational level. The challenge is in designing organizations (social work organizations, but also educational organizations such as the university) which do not exclude others. We get to know the approaches “Diversity Management” and “Intercultural Opening”. Diversity management began as a business strategy in the United States during the mid-1980s. Employee diversity is used in a resource-oriented manner and to gain profit in business enterprises and appeal to a wide range of customers. For example, single mothers championing the developments they see necessary in mini vans, which will benefit other single mothers as well (Schmitt/Tuider/Witte 2015). Or a financial institution which purposefully hired employees with a ‘Turkish background’. Those employees are in turn meant to win over customers with Turkish backgrounds (Arslan 2014). Although diversity management usually – but not always – follows economic principles, social justice is at the center of the approach of “Intercultural Opening”. The basic idea stems from a 1995 anthology titled “The Intercultural Opening of Social Services” (“Interkulturelle Öffnung sozialer Dienste”), by Klaus Barwig and Wolfgang Hinz-Rommel. The two authors advocate for a critical look at social services’ organizational structures and at unequal societal structures. Their concept was developed out of a critique. In the 1960s and 1970s, the diversity of language, the different nationalities and socializations of people with international backgrounds was seen largely as a problem, which was to be remedied through a “special pedagogy for foreigners”. “Social Services for Foreigners” and “pedagogical institutions for foreign employees and their families” were created (Mecheril 2010: 56). The children of so-called “guest-workers” were taught separately, in some cases. Barwig and Hinz-Rommel are critical of the creation of special, separate systems. They advocate viewing the diverse population not as a “problem”, social services and other societal institutions should rather be responsible for creating programs accessible to all. Examples for intercultural opening could be extending the internet times for young refugees in pedagogical resident groups, so that they can reach their family members and friends on Skype in other time zones (Schäfer 2013), checking your own facility for accessibility, writing flyers and homepages in easy language, supporting employees who are parents with flexible work hours or the possibility of working from home, recording the support of and taking into account diversity in mission statements, and making that support visible.

Conflict Areas in Diversity-Approaches

During the seminar, we discuss different examples of implementing diversity management and intercultural opening, during which the conflict areas become obvious. Diversity approaches focus on diversity, and therefore on differences between people. By focusing on those differences, however, it can be easy – and dangerous – to categorize people, seeing them first and foremost as “refugee”, “Muslim”, “woman”, “homosexual”. Such categorizations run the risk of being closely connected to stereotypes and lead to viewing everything a person says or does as ‘typical’ of a “refugee”, a “homosexual”, or a “Muslim”. It would be especially problematic if diversity approaches contribute to the creation and maintenance of a binary ‘us’ and ‘them’ difference from the perspective of the dominant culture (Kubisch 2003: 5). We can become aware of this area of conflict by critically broadening our views on the living situations and lives of others and reflecting on how and if we perceive, categorize, and address others. A further danger on the organizational level is that “well-meaning support” can tip: on the one hand, organizations want to cater to the specific needs of a diverse range of people, but on the other hand, target-group-oriented approaches can easily lead to a kind of negative specialization. The discussion of case examples allows questions of discrimination, racism, and participation to move to the center of our discourse, rather than reducing people to their culture.

Using Student Experiences and Recognizing them as Resources

Students regularly incorporate their own experiences in this seminar. They speak of what studying at the university as a parent is like, how it was to take part in mostly German-language seminars as a non-native German speaker, or of the challenges they face combining a (side) job with their studies. The participants’ experiences are a valuable resource. For one, they show the participants how “connected” we all are to the topic of diversity, and they also can act as impetus for the university’s development. It is a central and future-oriented task, then, to combine the students’ (and university employees’) perspectives together with organizational developments. Several seminar participants have continued working with the topic after the seminar had ended and written qualitative-empirical theses on the topic (see the interview with Kira-Maria Höll and Anne Pike). Examples of topics are “Student Discrimination Experiences at the University” or “Studying as a Young Mother”. The findings from these papers have provided a range of possible approaches for the university and specific, concrete hints on how institutional structures can be co-developed with a diverse student body.

Literature

Arslan, B. (2014): Beispiel für interkulturelle Öffnung in der Wirtschaft: Die Deutsche Bank AG. In: Mayer, C.-H./Vanderheiden, E. (Hrsg.): Handbuch Interkulturelle Öffnung. Grundlagen, Best Practice, Tools. Göttingen/Bristol: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, S. 250-251.

Aschenbrenner-Wellmann, B. (2009): Vielfalt, Anerkennung und Respekt. Die Bedeutung der Diversity-Kompetenz für die Soziale Arbeit. In: Sanders, K./Bock, M. (Hrsg.): Kundenorientierung – Partizipation – Respekt. Neue Ansätze in der Sozialen Arbeit. Wiesbaden: VS, S. 47-73.

Barwig, K./Hinz-Rommel, W. (Hrsg.) (1995): Interkulturelle Öffnung sozialer Dienste. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus.

Emmerich, M./Hormel, U. (2013): Heterogenität – Diversity – Intersektionaltät. Zur Logik sozialer Unterscheidungen in pädagogischen Semantiken der Differenz. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Kourabas, V./Mecheril, P. (2015): Von differenzaffirmativer zu diversitätsreflexiver Sozialer Arbeit. In: Sozialmagazin. Die Zeitschrift für Soziale Arbeit 9/10. Schwerpunktheft: Diversity und Soziale Arbeit, S. 22-29.

Kubisch, S. (2003): Wenn Unterschiede keinen Unterschied machen dürfen – Eine kritische Betrachtung von »Managing Diversity«. https://www.ash-berlin.eu/fileadmin/Daten/Einrichtungen/Frauenbeauftragte/Quer/07_2003/Auswahl_an_Artikeln_aus_der_Quer_07_2003.pdf (Stand: 24.04.2013).

Mecheril, P. (2010): Die Ordnung des erziehungswissenschaftlichen Diskurses in der Migrationsgesellschaft. In: Mecheril, P./Castro Varela, M. d. M./Dirim, İ./Kalpaka, A./Melter, C. (Hrsg.): Migrationspädagogik. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Juventa, S. 54-76.

Schäfer, A. (2013). Die Betreuung unbegleiteter minderjähriger Flüchtlinge als transnational orientierter Hilfekontext. In: Sozialmagazin. Die Zeitschrift für Soziale Arbeit 38, S. 62–71.

Schmitt, C./Tuider, E./Witte, M.D. (2015): Diversityansätze – Errungenschaften, Ambivalenzen und Herausforderungen. In: Sozialmagazin. Die Zeitschrift für Soziale Arbeit 9/10. Schwerpunktheft: Diversity und Soziale Arbeit, S. 6-13.

Timm, E. (2000): Kritik der „ethnischen Ökonomie“. In: PROKLA 120. Zeitschrift für kritische Sozialwissenschaft. Themenheft „Ethnisierung und Ökonomie“ 30, S. 363-376.

The “Hamburg Sie” is a form of addressing someone using their first name and the formal German “you” (“Sie”). This practice can aid in balancing the power inequality between teaching staff and students and therefore create a more welcoming environment. Addressing people with their first names and “Sie” can also allow for communication without gender classification – by avoiding addressing people with “Frau” or “Herr”, the – in the scientific community unnecessary – reminder of gender classification isn’t always present. Furthermore, unpleasant situations caused by improper pronunciation of someone’s last name can be avoided. This form of address can promote the inclusion of students with a migrant background or international students, since they are not always reminded of their “non-German” last name and the conveyed “difference” between them and other students. When implementing the “Hamburg Sie”, it is important for both sides to use it, so the imbalance of power isn’t emphasized even more.

A Student’s Experience:

During the first class of our seminar on the sociology of gender differentiation, our teacher suggested using the “Hamburg Sie”. He gave us the option of using either our first or last names during the introduction round. All of us decided on using our first names.

Especially during this seminar, during which we were focusing on the topic of gender and gender differentiation, the “Hamburg Sie” created the option to leave out our own gender affiliation (as far as possible). For me, it strengthened my self-perception as a researcher and not as a representative of a certain gender. It was unfamiliar, at first, to address a teacher by their first name, but the “Sie” created the necessary distance. So far, it’s worked really well and I think it would be great to experience it in other seminars.

Spending one or two semesters abroad is an almost integral part of studying for many students. But not every student feels like they have that Option. Depending on individual health, family, and financial situations, the experience to be had during a semester abroad doesn’t seem possible for some students. However, not everyone is aware that the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) has stipends available (for the ERASMUS program, for example) in order to cover additional expenses for people with certain life situations (children, chronic illnesses, handicaps, etc.), and BAföG can also be applied for on a semester abroad. A semester abroad with a child or a wheelchair requires a lot of planning, but the colleagues from the International Department are happy to help interested students with their preparation and with contacts to and experiences from previous students.

You as a teacher can support and encourage your students in their pursuit of a semester abroad and point them to the following support options:

- Advice on Studying Abroad from JGU (link in German)

- ERASMUS (link in German)

- Information on Studying Abroad from DAAD (link in German)

- International BAföG (link in German)

- A JGU Student Reports (link in German)

- ...

Faith in one’s own capabilities and competency in regard to overcoming difficult and challenging situations is an important factor in successful studies. Students with high expectation of self-efficacy find it comparatively easier to face challenging situations, and therefore deal with stress better. The respective amount of confidence in one’s own capabilities and competency is determined by different aspects, such as actual level of expertise, positive/negative prior experiences, learned behavior, discouragement or encouragement from the surrounding environment, fear of embarrassment, etc. The fear of being ridiculed or embarrassed or saying something wrong can thus negatively impact students. Students can be inhibited in participating in a seminar because they – for example – are not very familiar with the “academic type of discourse”, do not judge their knowledge or opinion to be relevant, have to overcome language barriers, or cannot cope with the pace of the class.

How can you as a member of the teaching staff support students with low expectations of self-efficacy?

- Teacher’s role: What is my own expectation of self-efficacy? How do I cope with challenging situations? Do I feel fear or strength in such situations? Do I think solution-oriented?

- Finding out and naming insecurities/ fears (individual conversations)

- Motivation: Encourage and point out successes

- Making sub-goals apparent and pointing out clear learning strategies (this is especially helpful for students with a heavy workload)

- Focus on the students’ strengths

- Establishing a positive culture around mistakes & creating discussion rules together (May 2016 – Rules & March 2016 – Welcome Culture)

- ...

Further literature on this topic:

Mucha, Anna & Christian Decker: Lernen ohne Angst vor Scham. In: duz 02/2018. S. 53 – 55.

Unconscious biases can be positive or negative biases based on gender, age, skin color, handicap, language, name, physical constitution, clothing, etc., which influence our perception of a person and therefore have an effect on our assessment of others and on our actions and decisions. On the one hand, these unconscious biases allow us to process information quickly and effectively, which can be vital – but they can often also be the source of errors in judgement and discrimination. Being aware of your unconscious biases can help minimize their negative effects. Harvard University’s Implicit project tries to make you aware of your unconscious biases and reflect on your own behavior or question its validity.

For teaching and learning situations, it can be worthwhile to reflect on the following:

- How much of a role does superior performance play in my grading?

- How do I feel when students speak in dialect?

- Do I make assumptions when a potential doctoral student becomes pregnant?

- What do I assume when I meet students in the lab or library late in the evening?

- What associations do I have when a student wears a headscarf?

- How do I feel when I notice someone coming late to my seminar at times?

- What impulse do I have when a student comes to an exam in flip-flops and shorts?

- How believable is an apology or excuse to me when the person speaking looks at the ground?

- …

In the Johannes Gutenberg University’s 2017 student diversity survey, 8% of students indicated they were chronically ill or handicapped. According to the 21st social survey of the German National Association for Student Affairs (Deutsches Studentenwerk), up to 11% of students have an impairment that negatively influences their studies. However, the impairment is only immediately noticeable for a small portion of these 11%, especially when it comes to chronic illnesses. Only a small number of the impaired students take advantage of advising and support offers or bring it up in a teaching and learning context.

From you as a teacher, these facts require sensitivity and an awareness of possible consequences of handicaps and chronic illnesses on the learning processes, as well as possible levels of influence and courses of action. Your contact at JGU is the Office of Accessibility

Our bodies are constantly being judged – by others, the media, ourselves – in a positive and negative sense. Body norms are relevant and applicable in daily university life, as well. If the way someone looks doesn’t match the supposedly valid norm regarding weight, size, length of hair, clothing, physique, or physiognomy, it can act as “trigger” for stigmatization and discrimination. Results from the previous JGU student diversity surveys named physical appearance as a risk factor for discrimination. Confronting this topic is therefore unavoidable for guaranteeing an inclusive university atmosphere. The following measures can prove helpful:

- Self-awareness: in which university situations am I aware of body norms / when does it play a role? Which associations and prejudices do I have? How large is that influence (on performance assessment, for example)?

- Avoiding stereotypes in the classroom

- Observance and promotion of diversity-oriented communication both for teaching staff and students

- Are you aware of instances in which students were discriminated against on the basis of their appearance?

- Handling and reacting to a situation: Initiate conversation, look for help or involve the counseling service

There are some teaching formats and situations which require close contact either between teaching staff and students, or also between students at times. This is true for subjects in which body contact between teaching staff and students is an unavoidable part of the lessons, such as musical education or sports, but also for teaching formats which require working in small groups, in the lab, outside of regular class times, or include personal experiences. Situations such as these require the teaching staff to be especially careful, respectful, and professional, and the students should also be encouraged to do so amongst each other. Here are some suggestions to avoid crossing any boundaries:

- Make clear to yourself and your students that the perception of proximity and distance differ from individual to individual;

- Announce body contact prior to touching someone and ask for permission or consent;

- Treat personal experiences with respect and never include them in a class without permission;

- Encourage your students to speak up if confronted with undesired behavior, and make it clear that you are available as a support and dialogue partner;

- Avoid comments about size, weight, looks, and physical constitution;

- Take appropriate action if you become aware of cases of sexual harassment or assault

- ...

Constructive feedback is an important basis for diversity-oriented teaching. Class-accompanying feedback from your students can help you tailor your classes to your students’ needs and address their potential. It’s important, however, to understand feedback as tool for development rather than an assessment of value. You should also give your students feedback systematically or promote giving each other feedback on presentations, homework, etc. In these cases, it’s especially important to look at the rules of giving (fair, constructive, prompt, I-statements, no exaggerations) and receiving (listening, not justifying yourself, seeing the information as optional) feedback and pointing these out to the students, if need be. Here are some helpful feedback methods you can use to continue developing your classes: